By Janet McGovern

When employees go to work three years from now in a new pre-treatment facility that is being built at the wastewater treatment plant in Redwood Shores, it will actually be a case of déjà vu all over again, thanks to an innovative design process that is letting them “see” the plant through virtual reality technology before the plans are finalized.

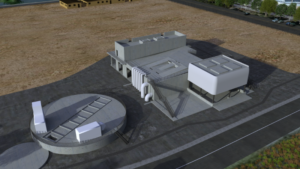

Virtual reality is being used in the design of the Front of Plant facility that is part of Silicon Valley Clean Water’s $495 million Regional Environmental Sewage Upgrade (RESCU) program, which serves some 220,000 residents and businesses in southern San Mateo County. The Front of Plant facility will fulfill a critical function in lifting up to the surface level wastewater arriving from four cities via gravity pipeline. From there, the wastewater will undergo the preliminary treatment process of screening and de-gritting in the state-of-the-art facility, then onto the main treatment plant where it will undergo further processing.

“For more than 40 years, our staff has dealt with rags and grit that get into our wastewater stream then into our pumps, valves, and other equipment,” said SVCW Manager Teresa Herrera. “This poses health and safety issues as well as environmental risks to our receiving waters. I am proud that we are finally able to remedy this situation.”

From the design to the construction phases, virtual reality technology is being used in the creation of the $138 million Front of Plant facility, something members of the Santa Clara Valley and San Francisco Bay sections of the California Water Environment Association got to see during a March 14 program in Foster City.

Greg Sturges and Aren Hansen of Brown and Caldwell gave the audience an overview of the technology, as well as a chance to experience it for themselves by strapping on a headset and “exploring” the Front of Plant model. (The model was developed by Parsons Corporation, a member of the Shea Parsons Joint Venture (SPJV) that is the design builder for the Front of Plant project. Brown and Caldwell is one of the firms that is working with SVCW and SPJV to ensure that the virtual design meets SVCW’s operational needs).

“It gives people a good idea of the facility even before it breaks ground,” Sturges said of virtual reality technology.

As Brown and Caldwell’s Lucas Cunningham operated a laptop, the employees from SVCW and other treatment facilities around the Bay got to travel from the top of the FOP to the floor of the facility 80 feet below, operating joysticks in both hands to navigate. They could pass like ghosts through giant pipes – and suddenly find themselves transported “outside.” With a click of a mouse, Cunningham could turn the sky from day to star-spangled night.

The experience can be a bit disorienting, Sturges and Hansen said, and a client typically has to get past the “wow factor” to really use the technology to examine a building under design before they’re ready to make use of it. (In fact, the safety plan includes a recovery chair where someone can take a timeout afterward – or is even feeling a touch of nausea.)

“The wow factor takes a little while to get used to,” Hansen said. “That’s why we’ve been down (to the treatment plant) a couple of times” with the designs, which were shown at about 60 percent completion for the demonstration. As employees get more comfortable wearing the goggles and using the joysticks to survey the virtual building, “you start figuring out ‘What do I want to get out of it?’ That’s the good part of it.”

For people who aren’t used to looking at plans on paper, being able to “walk around” a model makes it much easier to see what they’re looking at. And even if someone is used to reviewing paper plans, going through more than a thousand plans is a daunting and, likely, an impossible task especially for operators and mechanics who have their normal job duties to perform. This tool enables them to provide feedback to the designers in “real-time.”

For example, should there be more clearance around a pump shaft? Did designers consider all the space needed for maintenance and cleaning? Input from operations and maintenance employees is particularly valuable because they have hands-on knowledge and can give a designer feedback on the computerized model.

Said Hansen: “Even if the design engineer says ‘Oh, we’ve allowed two feet around all pipes,’ the operations person can say ‘Around those particular pipes, I’d like three.’” When the Front of Plant facility opens in 2022, SVCW employees will also know from day one what they need to do to run it and maintain it thanks to virtual reality.

In addition to the design benefits, the sophisticated technology can perform instantaneous calculations such as the cubic yards and cost of concrete that might be needed.

One of the other benefits of virtual reality design, Hansen said, is “matching expectations.” Even though people look at drawings and it’s on paper, they may still have different expectations; and virtual reality helps match up expectations to the design. “This shows pretty much what’s going to be built,” he said.